National Review: The Maker of Middle-earth, in Gorgeous Detail

This article was originally posted at National Review.

Oxford, England—After five months of ferocious and futile slaughter in “the Great War,” an Oxford undergraduate — knowing his deployment to the Western Front was inevitable — used his Christmas break in 1914 to cultivate his imagination. Twenty-two-year-old J. R. R. Tolkien began writing “The Story of Kullervo,” a heroic yet dark tale based on the Finnish saga The Kalevala. In May 1915, a year before he arrived in France as a second lieutenant in the British Expeditionary Force, he painted a watercolor, “The Shores of Faery,” which places Kor, the city of the Elves, at its center. Accompanying the painting, in his sketchbook, is a poem with the same name, describing Valinor, the “Undying Lands” that would form part of the landscape of his legendarium. Tolkien’s taste for fantasy, he explained, was “quickened to full life by war.”

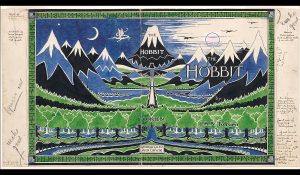

Such clues to the development of Tolkien’s creative imagination are beautifully assembled in “Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth,” an exhibition by the Bodleian Library of Oxford University that represents the most thorough treatment of his life and work in decades. The collection includes draft manuscripts of his best-known works, such as The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, as well as fan letters, family photographs, and dozens of drawings, maps, and watercolors that Tolkien created to illustrate his stories.

Indeed, the numerous sketches and paintings in the Bodleian’s Weston Library, which is hosting the exhibition, will enlighten even longtime Tolkien fans about the intensely visual and artistic aspect of his creativity. For many years, Tolkien’s four children — John, Michael, Christopher, and Priscilla — were the recipients of his “Father Christmas” letters, which usually included images drawn with ink or watercolor. His invented stories for his children ultimately led to The Hobbit (1937), and he brought to the manuscript a series of artistic renderings to flesh out his vision. “I never could draw,” he wrote to his publisher with characteristic modesty, “and the half-baked intimations of it seem wholly to have left me.” Nevertheless, Tolkien produced dozens of drawings and watercolors, like the enchantingly pastoral “Hobbiton,” to help capture the forests and mountains and fields of Middle-earth.

The Bodleian’s Tolkien archivist, Catherine McIlwaine, has given the exhibition a tremendous vitality by placing Tolkien in the full context of his life: his role as son, scholar, tutor, author, husband, father, and friend. On display is a tattered portion of Tolkien’s 1926 prose translation of Beowulf, the Old English epic poem that he studied and taught for most of his professional life. He considered it the “greatest of the surviving works of ancient English poetic art,” and his college lectures on the poem drew large and enthusiastic audiences. “Dear Prof. Tolkien,” begins a 1941 letter from Betty Bond, one of Tolkien’s students. “Some of us among the home students would like to tell you how much we have enjoyed your ‘Beowulf’ lectures this term, and to thank you not only for enlightening but also entertaining us for two hours a week. We hope that we shall now be able to face the terrors of schools [examinations] as fearlessly as Beowulf met Grendel!”

Other letters in the collection capture moments of intense poignancy. “Dear Daddy, I am so glad I am coming back to see you it is such a long time since we came away from you,” the four-year-old Tolkien (with the help of his nurse) wrote to his father, then working in South Africa. “I hope the ship will bring us all safe back to you.” A telegram arrived the same day, bringing the news that Arthur Tolkien was seriously ill. He died the following day, February 15, 1896. A letter from Geoffrey Smith, one of Tolkien’s inner circle of school friends, hints at the experience of loss that would inform so much of his literary work. Smith, who arrived at the Western Front shortly before Tolkien, wrote him from France: “May God bless you my dear John Ronald and may you say the things I have tried to say long after I am not there to say them, if such be my lot.” Smith was killed leading his men on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme, July 1, 1916.

One of Tolkien’s most famous tales is the love story of the mortal man, Beren, and the immortal Elf-maiden, Lúthien Tinúviel. He first told a version of the story in The Book of Lost Tales, which formed the basis for The Silmarillion. His hand-written manuscript begins thus:

Among the tales of sorrow and ruin that come down to us from the darkness of those days there are yet some that are fair in memory, in which amid weeping there is a sound of music . . . and under the shadow of death light that endureth.

As the exhibition explains, the legendary story of Beren and Lúthien was inspired by a true love story: the relationship between Tolkien and his wife, Edith, a marriage that endured for more than 60 years. A manuscript, written in Edith’s hand, forms the first chapter of The Book of Lost Tales, composed when Tolkien the soldier was recovering from trench fever. On Tolkien’s instructions, the names “Lúthien” and “Beren” are inscribed beneath their names on their shared headstone in Wovercote cemetery in north Oxford.

Implicit throughout the exhibition is Tolkien’s singular moral vision: a view of human life as both heroic and tragic. Here, it seems, is the motive force behind his astonishing creativity — an essentially Christian belief in the fall of man. In this, he was helped immeasurably by his circle of Oxford literary friends, the Inklings. All the members of the Inklings were professing Christians, and at the center of their weekly meetings was C.S. Lewis, another veteran of the Great War who became Tolkien’s closest friend for many years.

Lewis, also a lover of mythology and author of books such as The Chronicles of Narnia and The Screwtape Letters, was the first to challenge Tolkien to turn his private “hobbitry” into a published work. Tolkien confessed that he never would have completed The Lord of the Rings — a work twelve years in the making — without Lewis’s constant encouragement. “I have drained the rich cup and satisfied a long thirst,” Lewis wrote to Tolkien in 1949 after reading the story in manuscript. “So much of your whole life, so much of our joint life, so much of the war, so much that seemed to be slipping away . . . into the past, is now, in a sort, made permanent.”

Tolkien’s remarkable achievement was to use the genre of myth to reaffirm — against a culture of doubt and disillusionment — the “permanent things” about our lives, to engage his immense imaginative and artistic gifts to recover ancient truths about the human condition. Though often accused of escapism, no author in the 20th century expressed with greater power (as he once described it) “the beauty and mortality of the world.” The Bodleian exhibition richly tells the story of his quest: quickened while a soldier in the Great War; nurtured by his faith, family, and friendships; and deepened through sorrow and consolation. As Tolkien once described his great mythology: “It is written in my life blood.”

—

Joseph Loconte is an associate professor of history at The King’s College in New York City and the author of the New York Times bestseller A Hobbit, a Wardrobe, and a Great War. He is at work on a documentary film series based on the book, and the film trailer can be found at hobbitwardrobe.com